WHAT IT WAS ^ David Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.” began life as a television series pilot commissioned by ABC for the 1999-2000 season. Like Lynch’s legendary 1990-1991 foray into network television, “Twin Peaks” (which later spawned the criminally underrated 1992 prequel feature, “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me”), the engine driving the “Mulholland” pilot is a mystery centering on a young woman.

The pilot begins on a dark stretch of the titular, windy road in the Hollywood Hills, where said woman (Laura Elena Harring, a long way from doing the lambada in the 1990 camp classic “The Forbidden Dance”) narrowly escapes an attempted hit, thanks to a freak traffic accident. While she stumbles away from the scene with her life, she doesn’t come away with her memory, and she ultimately holes up in a nearby apartment that happens to be empty–at least when she first gets there; she is soon greeted by perky aspiring actress Betty (Naomi Watts), the fresh-from-Deep Water, Ontario niece of the apartment’s regular tenant. Betty and the amnesiac woman, who takes on the name “Rita” after looking at a poster for the Hayworth-starrer “Gilda,” become quick friends, and Betty vows to help Rita recover her lost past.

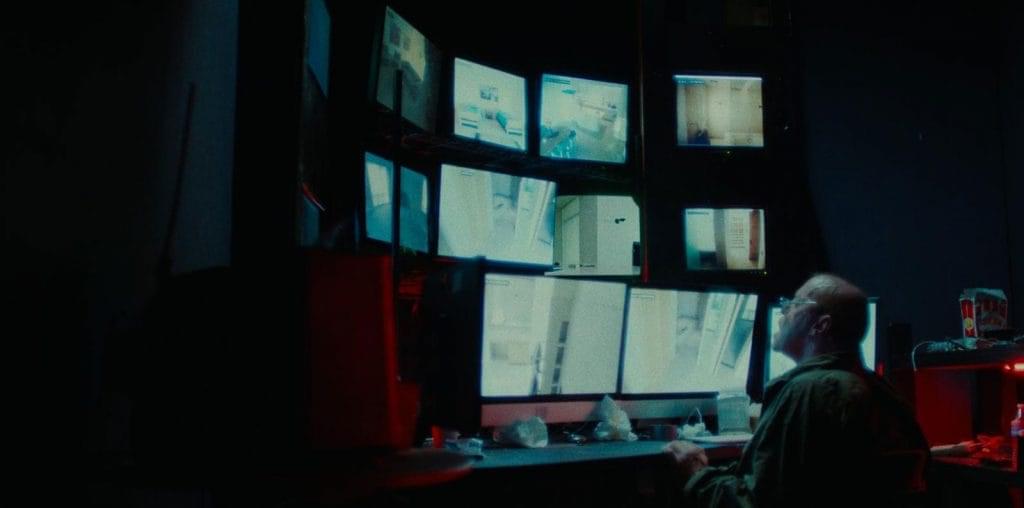

Also like “Peaks,” “Mulholland” is an ensemble piece, and while the Betty/Rita storyline is the main concern, there are other subplots that play out in the background. One that directly relates to the main story is that of a clumsy hitman (Mark Pellegrino) out to finish the job on Rita. Another major thread has less direct relation: one involving Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), a hot Hollywood director who’s being forced to surrender casting control–and perhaps more–to some mob types.

While the characters, setting, and situations, not to mention the more noir-based flavor, are quite distinct from “Peaks,” the pilot-based portion of “Mulholland Dr.” (which is rather easy to recognize as roughly the first 100 minutes of the film’s total 147-minute run time) more than recalls that earlier series. Some characters are even direct analogues to those in “Peaks”: Betty’s golly-gee enthusiasm at cracking a case is a more extreme take on FBI Agent Dale Cooper’s similar work attitude; the creepy mob figure who sits in a curtained room is played by none other than “Peaks”‘ diminutive curtained room resident Michæl J. Anderson, wearing an oversize body; and the information-imparting ways of the “Peaks” character of the Giant continue in the form of the Cowboy (Monty Montgomery). That character–and, in one standout sequence, the hitman–offers some scene-stealing doses of typically absurdist Lynchian humor. Most “Peaks”-ish of all is the unsettling, unpredictable atmosphere. Once again Lynch regular Angelo Badalamenti (who has a memorable cameo) composes a haunting, dread-filled score that highlights the underlying danger and evil that threatens to surface at any given moment.

WHAT IT COULD HAVE BEEN ^ ABC passed on “Mulholland Dr.” as a series, reportedly because higher-ups found it — shock of shocks — too weird. (The network instead went with “Wasteland,” the Kevin Williamson-created twentysomething drama that ended up flaming out after a scant two months on the air.) Based on the intoxicating narrative groundwork he establishes, there’s little doubt that Lynch could have had another watercooler sensation along the lines of first-season “Peaks.” If that series, with its focal families living in a small town filled with dirty secrets, can be seen as Lynch’s take on the old school TV soap, then all indications suggest that a regular “Mulholland Dr.” series would have been his uniquely off-kilter spin on the slick ’90s breed of sudser, with its young, Aaron Spelling-ready cast members (interestingly enough, Harring toiled for a year on that producer’s short-lived daytime drama “Sunset Beach”) intertwining in an apartment complex that–perhaps not so coincidentally–bears eerie resemblance to the “Melrose Place” compound.

WHAT IT BECAME ^ A year after “Mulholland Dr.” was officially pronounced dead as a television project (talks with other networks went nowhere), Lynch secured financing to morph his open-ended pilot into a self-contained feature. That the final 40 minutes or so do not offer a clean and conventional resolution to the many dangling threads that had been carefully introduced will certainly be a source of endless irritation to many a moviegoer. However, this should be a reason for relief; it’s not in Lynch’s blood to come up with tidy solutions, as so clearly illustrated by the half-hearted quickie wrap-up to the “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” mystery in the European version of the “Peaks” pilot.

Call it either brilliant or boggling (or maybe even both?), there’s no denying that the course that Lynch decided to take is nothing short of astonishing. Instead of serving up a capper to a previously unfinished work, he redefines the whole–or, rather, refines it. Most attention will be paid to the many surreal occurrences in this final stretch, but far more important than the surface trickery is what it accomplishes: redirect the focus from events and characters to the film’s raw emotional core. In scattering events and identities with seeming randomness, Lynch apparently says that such particulars are moot; what matters are the emotions boiling within the people–in particular, the person played by Watts, whose virtuoso performance is a wonder on par with the film’s daring transformation.

Perhaps nothing illustrates this better than “Mulholland Dr.”‘s most startling scene, where Betty and Rita go to a creepy nightclub/theatre and sit transfixed as a woman onstage warbles a heart-crushing, a cappella, Spanish version of Roy Orbison’s “Cryin’.” Just about everything about the scene has the air of the unreal–the strange woman with the blue hair in the box seating; the blurred lines between singing/speaking and lipsynching in the show, not to mention those between the languages–except the intimately devastating emotional impact of the singer’s lament of lost love (which proves to hold even more resonance as the film goes on).

At first glance, the simple, single-sentence–or, rather, “single-line,” since it’s technically just a phrase–synopsis offered in the “Mulholland Dr.” press kit appears to be a classic case of Lynch playing coy. But once one sees the maddening, masterful “Mulholland Dr.,” one would be hard-pressed to come up with a more accurate and appropriate description of the experience than “a love story in the city of dreams.”